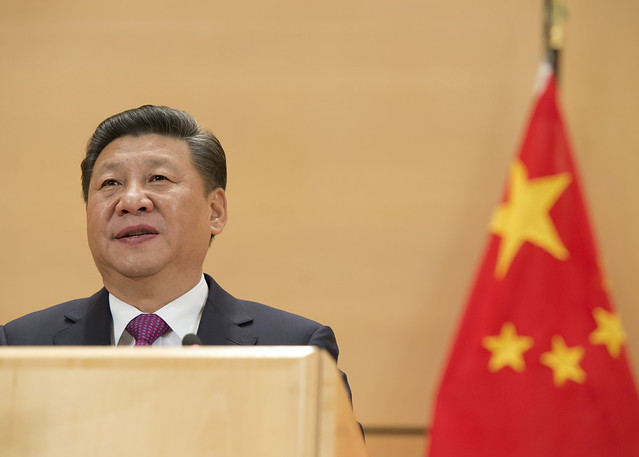

Practices of cyber-nationalism in China that are characterised by the meticulous control and surveillance of its cyberspaces have asserted global influence around political, social and economic dimensions, ultimately shaping the nation’s cyber future. Under President Xi Jinping’s leadership, China’s efforts in actively shaping the global internet are influenced by the views of cyber-sovereignty, developing laws to refrain from cyber hegemony and engagement towards national security threats (Segal, 2020). The technical and legal system, known as the Great Firewall, that ensures domestic stability and regime legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party encapsulates the desperation to challenge U.S world power (Toyama, 2018). Through, suppressing disinformation on Chinese cyber activities, preventing threats to privacy and concentrating on political and economic innovations to control data, China believes the overall goal of maintaining the government’s regime can be achieved.

Differences between China and the U.S

The heightened rivalry between China and the U.S as a global world power, dominating the cyberspace, reinforces the significance of practicing cyber-nationalism to gain political and economic attention. Stabilising leadership in the Chinese Communist Party (also known as the People’s Republic of China) is demonstrated through controlling media, offering national bias content, and using government agencies to promote patriotic ideology (Zhang & Qiu, 2022).

Chinese nationalism outlined in three developmental stages of nationalisation, modernisation and internationalisation (Li, 2009). is represented in The Belt and Road Initiative. This important economic policy advocated by government officials and its people have characterised a strong discourse that expresses hostile behaviours towards western countries who interfere with the success of widespread xenophobia (Clarke, 2017). The blame on the U.S for using its hard power to increase geopolitical supremacy, further contributes to the behaviours of extreme propaganda and censorship developed by China (Zhang & Qiu, 2022). Beijing’s influence on U.S companies have sparked concerns regarding the privacy of American citizens, after Apple removed an app that enabled protestors in Hong Kong to track and maliciously target individuals where no police officers were present. A tweet supporting Hong Kong protesters received backlash from Chinese authorities, leading to apologies by the N.B.A Houston Rockets and cancellation of games in China.

The top-down concept embodied by western countries accentuates the differences between U.S and Chinese intentions. They view Chinese nationalism as an expression of the ruling elite interests to succeed in a power vacuum in East Asia. Contradicting this perception, the bottom up view represented by China argues that nationalistic interests reflect the attitudes of citizens rather government motives (Ying, 2012). Hence, the growing tensions between the United States and China increased by cyber political differences and social behaviours online demonstrate the persistence of nationalism as a cause from wanting to dominate over the U.S.

The spread of disinformation

The purpose of disinformation developed by both Chinese and American parties have caused widespread disillusionment in respective societies, reinforcing and reflecting upon nationalistic measures to cultivate a global cyberspace that represents desired values. Further differences of the two nations are highlighted in their internet governance approaches. China advocates for a multilateral model that pushes for a government-driven internet landscape, challenging ICAAN’s multistakeholder model utilised by U.S and western allies (Wang, 2020). The two rival cyber-diplomacy and regulatory schemes that exists, instigates growing apprehension from the U.S towards China due to their nation utilising the language of internet freedom and sovereignty to justify the ethical intentions behind surveillance and suppression of free speech (Jiang, 2010). Consequently, western media has shaped the skewed perceptions of authoritarian control, painting the brutality of Chinese security through graphic images and official government YouTube videos. An example is the spoken experience of minorities in internment camps across areas in China.

Evidently, contradicting perspectives of the internment camps are evident. From claiming the camps support individuals with extremist thoughts to a criticised organisation that suppresses human rights. To further disclose the xenophobic efforts of Chinese campaigns, a Tik Tok that gained attention on the reality of camps was taken down by authorities to mask the truth, accusing the U.S of spreading disinformation.

Recent activities in 2023 that are linked to Chinese law enforcement is the identification of a Chinese disinformation campaign, spamouflage by Meta. The political spam network posted “positive commentary about China and Xinjiang province and criticisms of the US, western foreign policies” (Taylor, 2023). While, over 7,700 accounts and 930 pages on Facebook were discovered the disinformation network was ineffective as most of its followers were inauthentic. The spread of subjective western information highlights a contributing factor to cyber-nationalism and sovereignty, preventing the production and share of inaccurate social assumptions that may detriment China’s current governance.

Threats to privacy

Conversely, the threats to privacy by China’s forceful measures of cyber-espionage have overpowered the policies and protection of western nations resulting in a skewed cyber-sovereign webspace that weakens support for their rise as a global power. Cyber-security has raised concerns for the behaviours of internet crimes and cyber-terrorism occurring due to the fragmentation of the internet (Yeli, 2017). Chinese laws influenced by the lack of privacy protection in traditional Chinese culture differs with western countries who focus on expanding privacy rights to personal data collection (Pernot-Leplay, 2020). China increased series of high-level laws that excluded the consideration of personal information protection to safeguard national security as revealed in the 2012 National People’s Congress decision. To further highlight the importance of Chinese national security, the Cyber Security Law (CSL) that came into effect on 1 June 2017, represents the regulations used to create a heavily controlled sovereign cyberspace (Greenleaf & Livingston, 2016). This law is also thought to control the occurrence of cyber-attacks and fraud in China.

Contradictory, Chinese officials have manipulated the reports of state-sponsored hacking in the U.S by informing that China are frequent victims of cyberattacks by deeming them as collective disinformation campaigns. However, the cyber movements made in the U.S are still occurring in today’s age and are aimed to deter U.S involvement in Asia (Hjortdal, 2011). Warning from the U.S State Department on China’s capability to launch cyber-attacks against critical communications infrastructure demonstrates the use of cyber-espionage to produce extreme economic ramifications between the U.S and Asia. The threats to privacy through practices of cyber-espionage have cultivated ambitions for a nationalistic webspace, however it simultaneously reveals strained international relations from China’s preventive acts consequently affecting their rise to power and the overall success of cyber-nationalism.

Concentration of economic and political power by big technology firms

The focus on bolstering political and economic power within the development of the cyberspace has also influenced the problems of China achieving cyber-nationalism demonstrating strength as a world power. The push for a data sovereign country where information is subject to the laws and regulations of China, reveals a clear link to cyber-sovereignty and the overall goal of strengthening digital authoritarianism (Liu, 2021). The emergence of national digital borders has resulted in political conflicts, enacting The National Intelligence Law of 2017 to safeguard security and interests of the state (Ryan, Fritz & Impiombato, 2020). Due to laws declaring the right for data to be shared with Chinese intelligence-gathering authorities, the U.S have highlighted concerns over the data that could be shared from Tik Tok or Chinese telecommunications company, Huawei.

The ban of Huawei in the U.S and western allies sparked from the accusation of China using its 5G infrastructure for espionage on the U.S, threatens their national security and violate international sanctions. This has limited opportunities for China to share political influences in cyberspaces.

Economically, the Five-Year Plans were significant in setting out the strategic role that digital technologies were expected to play in national development (Jia & Winseck, 2018). China’s innovation economy is a political imperative because it drives the economic development into a higher-quality growth pattern. This is exercised in the Smart City strategy that introduces modern science and technology to urban planning, construction, and operation (Parasol, 2018). The fours tech companies, Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent and Xiaomi each specialising in different areas of technology regulate digital platforms in accordance with economic, political and social values (Dekker, Martin & Okano-Heijmans, 2021). While political power influences data driven markets to be controlled by Chinese Communist Party objectives, the tendency for monopolies to form in these markets may interfere with their digital policy agendas. This problem of reining monopolistic business practices have heightened the abuses of power, resulting in less innovations within the private sector and the dependency on state-led investments to boost economic growth that was affected during the pandemic. Hence, the concentration on accentuating political and economic power through technology firms has consequently led to a decline of stable, influential growth counteracting the developmental success of political and economic projects.

The contributing factors towards cyber-nationalism in China can be argued as somewhat successful because political, social and economic practices employed to control cyber activities is strengthening the government authority nationally but weakening its power internationally.

References

Aljazeera. (2023, March 16). China: US Spreading disinformation and suppressing Tik Tok. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/3/16/china-us-spreading-disinformation-and-suppressing-tiktok

Associated Press. (2018, December 19). Chinese internment camp exports to US. [YouTube Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BuXk6XizZiQ

Aziz, F. [@ferozaazizz]. (2019, November 27). [Twitter Post]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/ferozaazizz/status/1199670871532683264?lang=en

Berman, N., Maizland, L., & Chatzky, A. (2023, February 8). Is China’s Huawei a Threat to U.S National Security? https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-huawei-threat-us-national-security

Clarke, M. (2017). The Belt and Road Initiative: China’s New Grand Strategy? Asia Policy, 24, 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1353/asp.2017.0023

Collier, K. (2023, August 12). Top U.S cyber official offers ‘stark warning’ of potential attacks on infrastructure if tensions with China escalate. https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/security/top-us-cyber-official-warns-infrastructure-attack-risk-china-tensions-rcna99625

Dekker, B., Martin, X., & Okano-Heijmans, M. (2021). Dealing with foreign technology companies. Towards open and secure digital connectivity: Europe’s and Taiwan’s paths after the world’s first digital pandemic, 12-17. Clingendael Institute

Fertitta, T. [@Tilman Fertitta]. (2019, October 4). [Twitter Post]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/TilmanJFertitta/status/1180330287957495809?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1180330287957495809%7Ctwgr%5E5b79beb357fffee9e3415fca64d67dc19ae3e45e%7Ctwcon%5Es1_c10&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.npr.org%2F2019%2F10%2F07%2F767805936%2Fhouston-rockets-gm-apologizes-for-tweet-supporting-hong-kong-protesters

Fitzsimmons, J. (n.d). China’s Cyber Security Law: how prepared are you? https://www.controlrisks.com/campaigns/china-business/chinas-cyber-security-law

Goswami, R. (2023, August 29). Meta says it has disrupted a massive disinformation campaign linked to Chinese law enforcement. https://www.cnbc.com/2023/08/29/meta-disrupts-chinese-misinformation-network-linked-to-law-enforcement-.html

Greenleaf, G., & Livingston, S. (2016). China’s New Cybersecurity Law- Also a Data Privacy Law? University of New South Wales Law Research Series, 1-10.

Hackencoder. [@hackencoder]. (2021, October 20). [Top Safest Cybersecurity Countries]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CVQCwxlAT2/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Hale, E. (2019, October 10). Hong Kong protests: Apple pulls tracking app after China criticism. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/10/hong-kong-protests-apple-pulls-tracking-app-after-china-criticism

Hjortdal, M. (2011). China’s Use of Cyber Warfare: Espionage Meets Strategic Deterrence. Journal of Strategic Security, 4(2), 1-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.4.2.1

Jia, L., & Winseck, D. (2018). The political economy of Chinese internet companies: Financialization, concentration, and capitalization. International Communication Gazette, 80(1), 30–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048517742783

Jiang, M. (2010). Authoritarian informationalism: China’s approach to Internet sovereignty. SAIS Review of International Affairs, 30 (2), 71-89.

Jiang, Y. (2012). Cyber-Nationalism in China: Challenging Western Media Portrayals of Internet Censorship in China. University of Adelaide Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9780987171894

Lee, Y. N. (2021, June 29). China has gone “too far” in clamping down on big tech – that will hurt economic growth, says analyst. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/06/30/chinas-crackdown-on-tech-firms-will-hurt-economic-growth-says-analyst.html

Liu, L. (2021). The Rise of Data Politics: Digital China and the World. Stud Comp Int Dev, 56(1), 45-67. https://doi.org/10.1007%2Fs12116-021-09319-8

Miller, M. [@repmarymiller]. (2023, March 23). [The Chinese Communist Party should not be allowed to conduct psychological warfare on our children and spy on our phones]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/reel/CqJBOnMDt6C/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Li, M. (2009). Chinese nationalism in an unequal cyber war. China Media Research, 5(4), 63.

Pernot-Leplay, E. (2020). China’s Approach on Data Privacy Law: A Third Way Between the U.S and the EU? Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs, 8(1), 49- 117.

Ryan, F., Fritz, A., & Impiombato, D. (2020). TikTok privacy concerns and data collection. TikTok and WeChat: Curating and controlling global information flows, 36–42.

Satter, R., Siddiqui, Z., & Pearson, J. (2023, May 26). U.S warns China could hack infrastructure, including pipelines, rail systems. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-rejects-claim-it-is-spying-western-critical-infrastructure-2023-05-25/

Segal, A. (2020). China’s Vision for Cyber Sovereignty and the Global Governance of Cyberspace. In N. Rolland (Ed.), An Emerging China-Centric Order: China’s Vision for a New World Order in Practice (pp. 85-100). The National Bureau of Asian Research.

Sherman, J. (2019, October 30). How Much Cyber Sovereignty is Too Much Cyber Sovereignty? https://www.cfr.org/blog/how-much-cyber-sovereignty-too-much-cyber-sovereignty

Taylor, J. (2023, August 30). Meta closes nearly 9,000 Facebook and Instagram accounts linked to Chinese ‘Spamouflage’ foreign influence campaign. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/aug/30/meta-facebook-instagram-shuts-down-spamouflage-network-china-foreign-influence

Toyama, K. (2018). The Great Digital China. China Review International, 25, 265-269. https://doi.org/10.1353/cri.2018.0062

UN Geneva. (2017, January 18). Official visit of the President of China. [Photo of President]. https://www.flickr.com/photos/unisgeneva/32270494731/

Wang, A. (2020). Cyber Sovereignty At Its Boldest: A Chinese Perspective. The Ohio State Technology Law Journal, 16(2), 395-466.

Web Summit. (2021, November 18). Huawei. [Photo of logo]. https://www.flickr.com/photos/websummit/51689379790

Wong, A. (2022, July 14). China’s big tech problem: even in a state-managed economy, digital companies grow too powerful. https://theconversation.com/chinas-big-tech-problem-even-in-a-state-managed-economy-digital-companies-grow-too-powerful-186722

Yeli, H. (2017). A Three-Perspective Theory of Cyber Sovereignty. Prism: A Journal of the Center for Complex Operations, 7(2), 109-115.

Zhang, D., & Qiu, X. (2022). Cyber-Nationalism in China: Popular Discourse on China’s Belt Road. In J. Rajaoson, R. M. M. Edimo (Eds.), New Nationalisms and China’s Belt and Road Initiative (143-156). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08526-0_11#DOI